Inger Pauline (Braaten) Hovick (1884–1975)

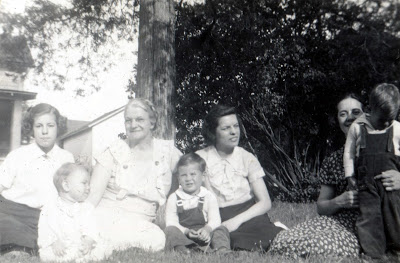

My maternal grandmother, Inger Pauline Braaten, known as Pauline, was born on 29 January 1884 in Fergus Falls, Otter Tail County, Minnesota. She was the daughter of Mikkel Mikkelsen Braaten (1 April 1834–28 January 1901), a dairy farmer and carpenter, and Gunhild Mathea Johannesdatter Pedersen Braaten (17 October 1844–18 April 1921), known as Mathea. Both were immigrants from Norway, both had been married before and widowed, and both had lost one child. Mikkel had six surviving children and Mathea had five, giving Pauline eleven half-siblings (see family tree below). Together, Mikkel and Mathea had two children, Pauline (29 January 1884–15 August 1975), and Johan Arndt (16 June 1886–3 February 1887).

At the age of sixteen, Pauline decided to become a nurse. Boarding a train to Chicago, she enrolled at the Norwegian Lutheran Deaconess Hospital on 15 October 1900, and was ultimately consecrated a Deaconess Sister. [1] Begun in Germany in 1836, the Deaconess movement quickly spread through Protestant denominations in Europe and the United States, most actively among Lutherans. Not unlike Roman Catholic nuns, Deaconess sisters lived in community in motherhouses, and were dedicated to nursing. Sisters went through a rite of consecration but were free to leave at any time to marry or to care for family. [2]

Pauline graduated in 1903. Her hometown of Fergus Falls offered her the position of Hospital Matron, but she declined, and instead became Head Nurse of the City Hospital of Madison, Minnesota. Shortly after arriving in Madison, she met her soon-to-be husband, Charles Hovick (2 May 1873–22 February 1848). Born Tjerand Torbjørnsen on the Håvik farm in Skjold Parish, Rogaland County, Norway, Charles ran the grain elevator in Madison. They were married in a grand double wedding on 18 May 1904. Likely because of societal expectations, Pauline gave up her nursing career after she married.

Pauline and Charles had four children: Tarald Melvin Hovick, who was stillborn on 26 June 1905 due to bad fall that Pauline had taken the day before, Mildred Ingeborg (Hovick) Monge (12 April 1907–16 November 2003), Signe Alise (Hovick) Christeson (3 August 1912–

15 July 2012), and my mother, Charlotte Pauline (Hovick) Thompson Lohman (9 October 1925–

8 November 2015).

In 1926, determined that their three daughters receive a quality education, they sold their farm in Madison and moved to Northfield, Minnesota so that the girls could attend St. Olaf College. Pauline spent years as a housemother at a boarding house for male college students, and Charles spent the rest of his life as a janitor at St. Olaf. Charles died of liver cancer on 22 February 1948. Pauline died on 15 August 1975 of heart failure after having broken her hip months earlier. She and Charles are buried in the Oaklawn Cemetery in Northfield, Minnesota.

[1] Mildred Hovick Monge, “Remember,” family history, 1974; “Remember,” blog entry, Hovick Lohman History, blog (hovicklohmanhistory.blog/remember/ : accessed 30 August 2020), pdf, pt. 1, ch. 4, “Recollections with Pauline,” p. 49 (printed).

[2] “The Deaconess Movement in 19th-Century America: Pioneer Professional Women,” United Church of Christ (www.ucc.org/about-us_hidden-histories_the-deaconess-movement-in : accessed 27 September 2020).

Pauline’s Family Tree