My father, Richard Byron Lohman (1924-2004)

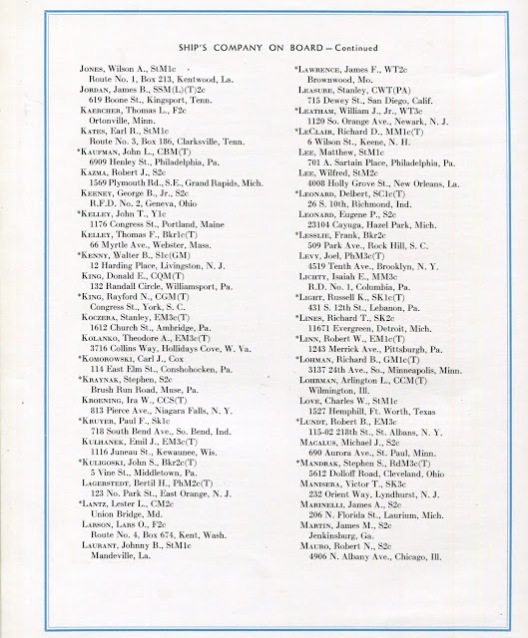

Gunner’s Mate First Class, USS General A.E. Anderson

Only hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Japan attacked the Philippine Islands. American forces had already been stationed there under the command of General Douglas MacArthur. The Allied American and Philippine forces attempted to defend the islands with outdated weapons and low supplies. On March 12, 1942, under orders from President Roosevelt, General MacArthur and a few select officers left the Philippines, promising to return with reinforcements. The abandoned Allied forces, fighting on the Bataan Peninsula and struggling with disease and malnourishment, eventually surrendered to the Japanese on April 9, 1942. It was the largest surrender in US military history.

Thus began the Bataan Death March, one of World War II’s many atrocities. 72,000 prisoners were forcibly relocated to the now Japanese-controlled Camp O’Donnell. By the end of the 60-mile march, an estimate 20,000 prisoners had died from illness, hunger, torture, and murder.

From there, prisoners were transferred to several prison camps. Almost three years later, by January of 1945, just over 500 American and Allied POW’s were being kept under brutal conditions at the Cabanatuan prison camp. On January 30, 1945, in what is known as The Great Raid, Allied forces liberated the camp and freed the prisoners.

A memorial, erected in 1982, now marks the location of the camp.

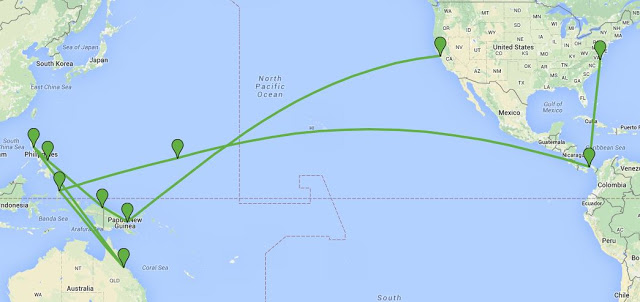

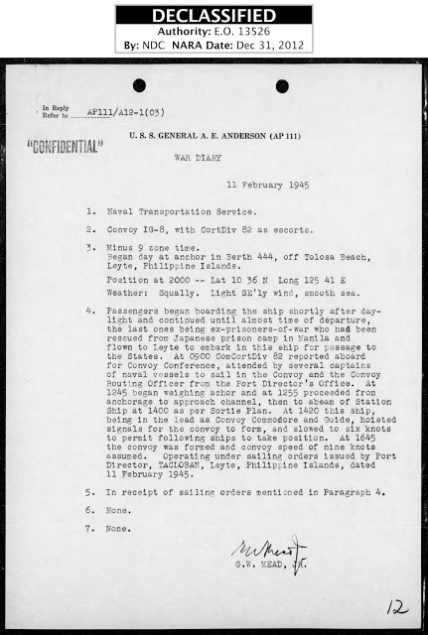

Many survivors were quickly flown back to the United States. However, those too sick to travel remained at American hospitals to recuperate. Almost two weeks later, on February 11, at the Philippine island of Leyte, the final 272/280 former POW’s were loaded onto my dad’s ship – the USS General A.E. Anderson – for their trip home to San Francisco.

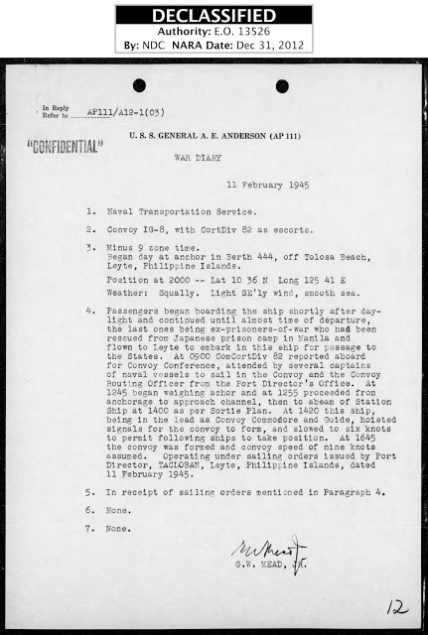

From the now-declassified War Diary of the USS General A.E. Anderson, dated March 8, 1945:

“Passengers began boarding the ship shortly after daylight and continued until almost time of departure, the last ones being ex-prisoners-of-war who had been rescued from Japanese prison camp in Manila and flows to Leyte to embark in this ship for passage to the States. At 0900 ComCortDiv 82 reported aboard for Convoy Conference, attended by several captains of naval vessels to sail in the Convoy and the Convoy Routing Officer from the Port Director’s Office. At 1245 began weighing achor and at 1255 proceeded from anchorage to approach channel, then to abeam of Station Ship at 1400 as per Sortie Plan. At 1420 this ship, being in the lead as Convoy Commodore and Guide, hoisted signals for the convoy to form, and slowed to six knots to permit following ships to take position. At 1645 the convoy was formed and convoy speed of nine knots assumed. Operating under sailing orders issued by Port Director, TACLOBAN, Leyte, Philippine Islands, dated 11 February 1945.”

From the USS General A.E. Anderson’s website:

“Most important to this voyage, we loaded several hundred of the survivors of the Bataan Death March. These soldiers had spent most of the war as prisoners trying to survive under the brutal, starving conditions of the prison camps. Many had to be carried aboard and were taken directly to the sick bay. Others were able to walk on board and spent the return trip home stoking calories.”

The camp’s liberation proved to give American morale a boost, and was a blow to the Japanese. In response, Japanese propaganda radio announcers (generically referred to as Tokyo Rose) warned that submarines, ships, and planes were hunting the Anderson. The threats proved to be a bluff, and the ship arrived safely in San Francisco Bay on March 8, 1945.

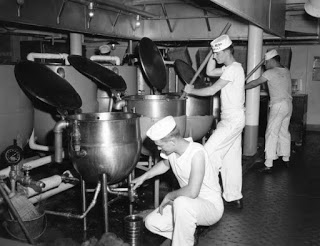

Dad’s most searing memory of that voyage home was seeing one of the survivors sitting in the mess room with a full plate of food before him. However, the soldier didn’t eat. He simply stared at his plate and wept.

|

| Mess Room aboard the USS General A.E. Anderson |

By the time they reached San Francisco and passed under the Golden Gate Bridge, Dad said that it seemed like every boat in San Francisco Bay was out to welcome these heroes home.

From the now-declassified War Diary of the USS General A.E. Anderson, dated March 8, 1945:

“Steaming independently with returning troops, naval personnel, and ex-prisoners of war on board, en route from Hollandia, NG, to San Francisco, California. … At dawn vessel was approaching San Francisco, with Farallones in sight. Day extremely clear and visibility excellent. Met by blimp escort. As 0806 passed Buoy “A” and entered mine-swept channel; thence to pilot station for pilot, thence up Main Ship Channel to under the Golden Gate Bridge at 1001. Passed through the nets as 1012 to accompaniment of whistles and sirens from welcoming ships and reception parties for ex-prisoners of war. At 1036 dropped anchor to await berthing instructions. Reception committees came aboard. As 1135 docking pilot came aboard and at 1148 anchor was aweigh and vessel proceeding to dock. At 1210 first line went ashore and vessel made fast starboard side to south side of Pier 15, San Francisco, California. Dock crowded with friends and relatives of ex-prisoners of war. Dis-embarkation began almost immediately and continued throughout afternoon until all passengers were off the ship. Liberty for the crew.”

“March 8, gliding under the Golden Gate and into San Francisco Bay, we were met by a blimp, sea planes, airplanes, boats of all sizes, whistles, horns and sirens. Fire boats were spewing huge fans of water and the Mayor’s welcoming party came aboard. Relatives waited for the prisoners-of-war at the dock for an unbelievable welcome home.”

|

| The San Francisco Mayor’s welcoming party |

Because of military security, the press was not allowed to report that it was the Anderson that carried these men home.

|

| San Francisco Chronicle – March 9, 1945 |

Click for a full-sized pdf

Again, from the Anderson’s website:

“We owned the town that night. It was one big party, a very special first night on shore. If you were from the ANDY, there was no way you could buy your own beer.”

More history:

Here is an American propaganda piece on this return of POW’s.

The experiences of Harold Malcolm Amos, who enlisted at the age of 18 when he weighed 205 pounds. When he was rescued from Cabanatuan, he weighed a mere 97 pounds.